Warren weighs her options. Endorsing Sanders is probably No. 1.

Super Tuesday was a fantastic day for Joe Biden. It was a disappointing day for Bernie Sanders, although he won a few states, including the largest in the union. And it was a disastrous day for Elizabeth Warren.

After finishing third in Iowa, fourth in New Hampshire, fourth in Nevada and fifth in South Carolina, the Massachusetts senator who was briefly the Democratic frontrunner met the 15 percent delegate threshold in just six of the 15 states and territories that voted Tuesday — barely clearing it in five of the six. And even in the state where Warren did best, she still lost to both Biden and Sanders. The fact that it was her home state of Massachusetts added insult to injury.

All told, Warren emerged from Super Tuesday — a day when 1,357 delegates were up for grabs — with a gain of just 36 delegates, for a total of around 60, compared with more than 500 for both Sanders and Biden.

So if it wasn’t clear before, it’s abundantly clear now: Warren has no path to winning the Democratic nomination.

The question is, what will she do next?

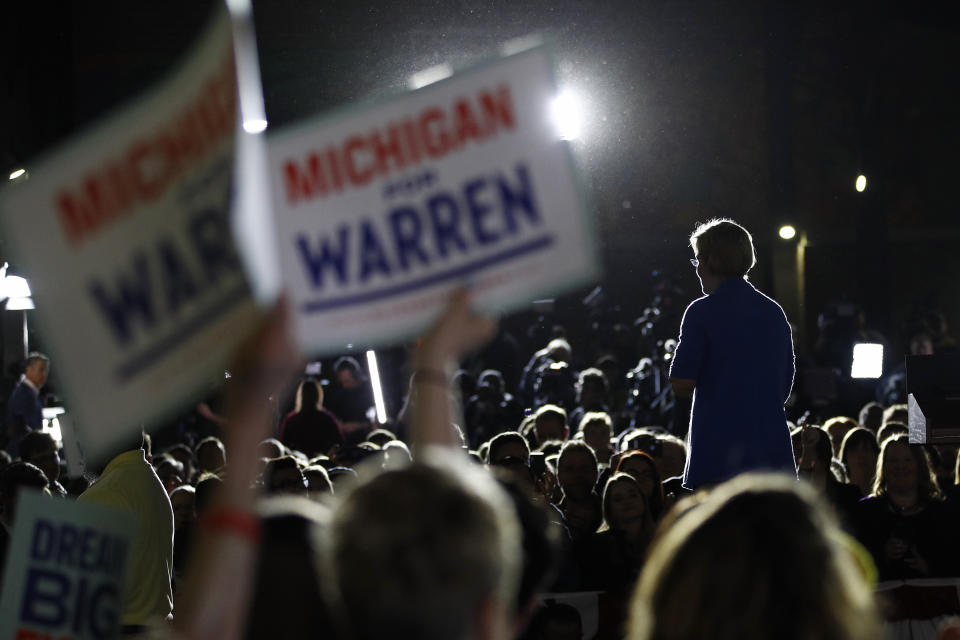

She hasn’t said. After a rally in Detroit, Warren flew home to Boston late Tuesday. She has no public events scheduled Wednesday. A senior campaign official told The Hill she would meet with staff to consider her options.

“Elizabeth is talking to her team to assess the path forward,” the aide said.

Before Tuesday, Warren’s team was pushing the idea that their boss would barrel through to a contested convention. On Sunday, Warren campaign manager Roger Lau openly predicted that “no candidate will likely have a path to the majority of delegates needed to win an outright claim to the Democratic nomination.”

“Milwaukee is the final play,” he continued, referring to the site of July’s Democratic National Convention. It was there, Lau said, that Warren would “ultimately prevail.”

But Warren’s dismal Super Tuesday showing makes that an untenable strategy. Either Biden or Sanders could theoretically suffer a campaign meltdown in the weeks ahead — but the other would still be standing in Warren’s way. Meanwhile, Warren would have to keep campaigning (and likely losing) while asking her supporters, staffers and volunteers to keep working for a lost cause.

There was some speculation, meanwhile, that even if Warren didn’t win the nomination at a contested convention, she could position herself as a kingmaker of sorts — an influential figure with the power to send her delegates one way or the other in exchange for a Cabinet position or the vice presidency or some other substantial prize. But 60 delegates is far fewer than Warren hoped to have at this point, and unless the primaries end in a virtual dead heat they won’t be enough to make a difference.

So Super Tuesday has shortened Warren’s time frame. Instead of strategizing about Milwaukee, she has to figure out how she can leverage her remaining influence right now.

On Wednesday morning, former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg provided one example. Like former South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg and Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar before him, Bloomberg dropped out and endorsed Biden, arguing (like the others) that “defeating Donald Trump starts with uniting behind the candidate with the best shot to do it.”

But Warren is a progressive, not a moderate, and she has repeatedly signaled that she doesn’t believe Biden is the “best” candidate to beat Trump.

“I respect his years of service,” she said Monday night during a rally in Los Angeles. “But no matter how many Washington insiders tell you to support him, nominating their fellow Washington insider will not meet this moment.”

“Nominating a man who says we do not need any fundamental change in this country will not meet this moment,” Warren continued. “Nominating someone who wants to restore the world before Donald Trump, when the status quo has been leaving more and more people behind for decades, is a big risk for our party and our country.”

Warren and Biden also have history: They battled throughout the 1990s and early 2000s over bankruptcy reform, and no love was lost between them. Unless Biden suddenly offers Warren the vice presidency — and leeway to make “big, structural change” under his potential administration — it’s very hard to imagine her coming onboard.

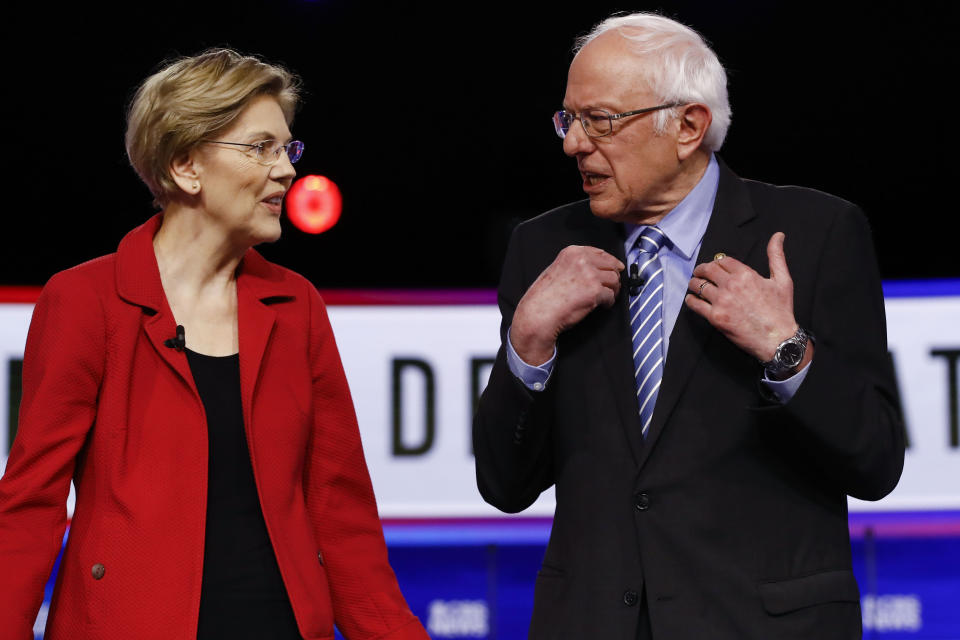

That leaves Sanders.

For days, Sanders supporters have argued on social media and elsewhere that Warren was playing the spoiler for progressives while the “establishment” was rallying around Biden in the wake of his South Carolina landslide. But Bloomberg and Warren earned a roughly equal number of votes on Tuesday, and not all Warren supporters name Sanders as their second choice. So it’s unclear that the day would have unfolded much differently if only Biden and Bernie had been on the ballot.

What is clear is that if Sanders wants to compete with a resurgent Biden going forward, he needs Warren on his side.

At a press conference he called to discuss the Super Tuesday results, Sanders said he had spoken to Warren on Wednesday, although he didn’t describe their conversation.

The case for Sanders and Warren to team up is twofold. The first part has to do with messaging. As New York magazine’s Eric Levitz has pointed out, “Sanders declined to adopt the posture of a magnanimous frontrunner” after winning Nevada, choosing instead to continue campaigning “as an insurgent” and “to paint his Democratic rivals — almost all of whom are quite popular among Democratic primary voters — as unscrupulous shills for corporate power.” This strategy likely provoked a backlash on Super Tuesday, both among former Buttigieg and Klobuchar supporters who’d been made to feel unwelcome in Sanders’s “movement” and among late deciders looking for a candidate more interested in unifying the party than criticizing it.

This is a problem Warren could help solve — first because endorsing Sanders would instantly convey unity on the left, and second because she’s already spent the entire campaign presenting progressive, populist ideas in ways that are palatable to the professional-class voters now gravitating toward Biden, something she could continue to do alongside Sanders on the stump.

And that tees up the second part of the Sanders-Warren solidarity argument: demographics. According to the Super Tuesday exit polls, Sanders ran strongest among young voters, Latino voters and white voters — particularly white male voters — without a college degree. Warren overperformed among college graduates — particularly female college graduates in places like Minnesota.

A big reason why Biden came roaring back on Super Tuesday is that affluent suburban voters — especially suburban women in Virginia, North Carolina, Texas, Minnesota and Massachusetts — broke for him over Sanders. Joining forces with Warren wouldn’t necessarily sway all of them to Sanders’s side. But with the wind at Biden’s back and a flurry of Biden-friendly states still to come on the calendar, what better chance does Sanders have than to partner up with a woman who holds a particular appeal to the voters he most needs to win over in order to stay afloat?

As to what’s in it for Warren, who knows? But after a terrible Super Tuesday, she’s running out of other options to make a difference in 2020.

Read more from Yahoo News: