Warren's big applause line — abolish the Electoral College — gets picked up on the campaign trail

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

The first problem is deciding whether it is a problem.

As laid out in the Constitution, the people of the United States don’t technically elect the president. Their votes elect members of an Electoral College, and each state is assigned a certain number of these “electors,” determined by its number of representatives in the Senate and the House, for a total of 538.

In almost every state, the presidential candidate who gets a plurality of the votes in that state gets all of its electors. This is why maps turn red and blue on TV on election night, and why the candidate who achieves 270 electoral votes or more becomes president. Technically, though, the president is not chosen until the electors vote in December and Congress certifies the result in January.

The potential problem is that the electoral vote does not always reflect the popular vote, the tally of individual votes cast nationwide. Historically, the winner of the popular vote is usually also the winner of the electoral vote, but not always. Five times in 200 years the winner of the electoral vote has lost the popular one. Two of the last three presidents were elected that way — George W. Bush in 2000 and Donald Trump in 2016 — leading to much debate recently over whether the system should be changed.

Those who think this is problematic — including at least 13 declared candidates for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination — say that allowing the popular vote to choose the president “would be reassuring from the perspective of believing we’re a democracy,” as South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg put it.

But those who feel change is unnecessary, including the current president of the United States (at least now; he had opposed the Electoral College before he became its beneficiary), believe the Founding Fathers had good reasons for creating the system in the first place.

The Electoral College was the result of a series of compromises. Early drafts of the Constitution gave the power to choose a president directly to Congress, but that idea was rejected by many delegates as a violation of the idea of separation of powers. Other proposals allowed state legislatures to decide, but this too was rejected, for fear that the president would be beholden to the states. And the idea that the people could decide directly was considered unworkable at the time. Delegates believed that a tyrant could too easily manipulate the (presumably ill-informed) population and seize power.

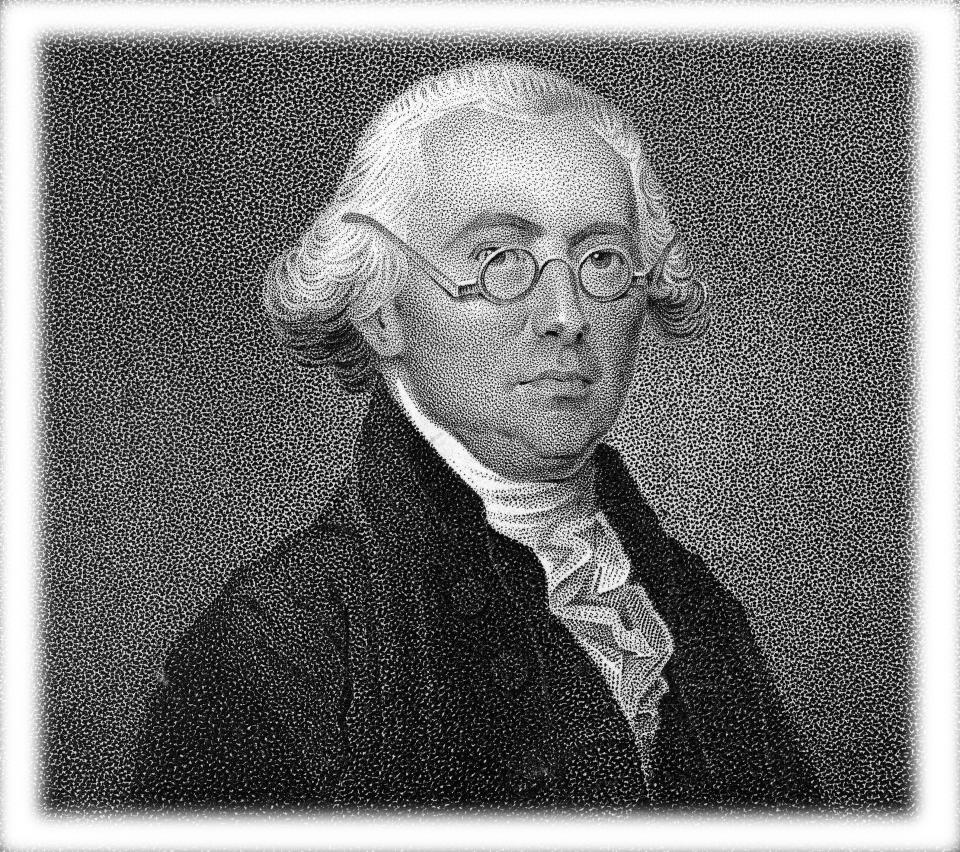

Eventually James Wilson of Philadelphia (who would go on to be one of the first six justices of the Supreme Court) proposed the idea of a group of electors who would vote in proportion to the population of their states. This would satisfy the representatives of smaller states by assuring that candidates were not beholden just to the interests of the largest population centers. It would also create a bridge and buffer between the raw vote of the people and what was presumed to be the cooler heads of the ruling classes.

Wilson’s version became Article II, Section 1, clauses 2 and 3 of the Constitution – “each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress” — and also the 12th Amendment, passed in 1804, specifying that the electors vote separately for the president and vice president.

Over the centuries, many have taken aim at the Electoral College. About 700 congressional proposals have suggesting abolishing or altering it, more than any other part of the Constitution. In 1966 Sen. Birch Bayh of Indiana, who had successfully sponsored both the 25th and 26th amendments, began a campaign to eliminate the Electoral College. Jesse Wegman, a member of the New York Times editorial board and the author of “Let the People Pick the President,” to be published in 2020, wrote in an essay in March:

“In a remarkable speech on May 18, 1966, Mr. Bayh said the hearings had convinced him that the Electoral College was no longer compatible with the values of American democracy, if it had ever been. The founders who created it excluded everyone other than landowning white men from voting. But virtually every development in the two centuries since — giving the vote to African-Americans and women, switching to popular elections of senators and the establishment of the one-person-one-vote principle, to name a few — had moved the country in the opposite direction.”

In addition, Bayh argued, the winner-take-all method means candidates focus their campaigns on a small number of battleground states, largely ignoring the rest of the country.

A Gallup poll in 1968 found that 80 percent of the country supported election of the president by popular vote. The House voted for it in 1969, and the idea had the support of President Richard Nixon and appeared to be popular in a majority of state legislatures. But it was blocked in the Senate by Southern segregationists who thought it would encourage higher African-American turnout.

To amend the Constitution requires a two-thirds majority vote of both the House and the Senate, and then ratification by three-quarters of the states (38 of the current 50). Without the support of the Senate, Bayh’s amendment was dead.

The idea of changing the way Americans elect their presidents has been much talked about on the presidential primary trail. Thirteen Democratic candidates have come out in favor of the popular vote — Buttigieg, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke, Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, former HUD Secretary Julián Castro, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet, former Alaska Sen. Mike Gravel, Massachusetts Rep. Seth Moulton, California Rep. Eric Swalwell, Miramar, Fla., Mayor Wayne Messam and new age spiritual author Marianne Williamson.

Another five say they are open to the idea of reform — California Sen. Kamala Harris, Hawaii Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, Ohio Rep. Tim Ryan, independent Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar — while three oppose change, though more because “trying to abolish the Electoral College now is impractical,” as former Maryland Rep. John Delaney put it, than because they think it is the optimal system. (Former tech executive Andrew Yang and former Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper agree with Delaney, while former Vice President Joe Biden, Montana Gov. Steve Bullock and New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio have made no public statements on the subject.)

But how exactly do the candidates propose to bring about such change? A few have advocated the most obvious plan, the one Bayh and others tried — a constitutional amendment. In early April, Gillibrand co-sponsored such an amendment with fellow Democratic Sens. Dick Durbin of Illinois and Dianne Feinstein of California.

"I believe we need a constitutional amendment that protects the right to vote for every American citizen and to make sure that vote gets counted," said Elizabeth Warren at a CNN town hall in March, in a statement she uses at most campaign appearances around the country. "We can have national voting, and that means get rid of the Electoral College.”

But there is also another idea out there, one that does not involve changing the Constitution, with its cumbersome requirement of first congressional and then state-by-state approval. Rather than eliminating the electors from each state, it instead would change state laws about who those electors are authorized to vote for. There is nothing in the Constitution that requires the winner-take-all system, which evolved over the course of the 19th century. Already two states. Maine and Nebraska, use a proportional system — delivering some of their electoral votes according to the percentage of the popular vote each candidate received in the state. And an entity known as the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact would provide a third option.

A state legislature that signs on to the compact would agree that, in the event of a conflict between the electoral vote (as calculated under the existing system) and the total national popular vote, the electors from its state would all give their votes to the candidate who won the national popular vote, regardless of which candidate carried the state. The plan, which would make the Electoral College symbolic, would take effect only when and if enough states sign up to constitute a majority (270 votes) in the Electoral College.

At the moment, 14 states and the District of Columbia have signed on to the compact, representing a total of 189 electoral votes.

Several of the current Democratic nominees are promoting this approach. The group needs just "a few more states" to put the compact into effect, Inslee has said, “so you can essentially effectuate the popular vote even without a constitutional amendment. ... I believe that it’s time to have popular elections so the people’s vote decides who the president is, rather than the Electoral College."

That Democrats are in favor of eliminating the Electoral College is logical. It was two of their own who lost the electoral vote while winning the popular one in recent years.

Republicans, on the other hand, tend to defend the current system, because concentrating power in smaller states offsets the fact that there are nearly 12 million more registered Democrats than Republicans in the country at the moment.

Not surprisingly, most of the states that have signed on to the compact have Democratic legislative majorities and populations who voted for Hillary Clinton in the last election. Exceptions to that trend are therefore notable — such as the 40-16 vote in the Arizona House and the 28-18 vote in the Oklahoma Senate (the other body in those states has not yet voted on the compact). Nonetheless, reaching 270 is described as “difficult” by even the compact’s supporters.

Republican leaders stress this potential loss of power by smaller states when making their case for keeping the current system.

Although President Trump tweeted his dissatisfaction with the Electoral College back in 2008, when Obama was elected, he developed a new fondness for it in 2016, when he lost the popular vote to Hillary Clinton by nearly 3 million votes but won the electoral tally by what he describes as a historic landslide. In 2012, Trump called the Electoral College a “disaster for a democracy.” More recently, however, he tweeted exactly the opposite — that if the Electoral College were eliminated, smaller states “would end up losing all power.”

Smaller states would, of course, still have vastly disproportionate power in the Senate, where Wyoming and Delaware each have the same representation as California or Texas.

Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., also weighed in on Twitter, saying the Electoral College “makes sure the interests of less populated areas aren’t ignored at the expense of densely populated areas.”

Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., agreed, tweeting: “The desire to abolish the Electoral College is driven by the idea Democrats want rural America to go away politically.”

Some far-right activists go a step further, suggesting that the Electoral College protects white voters. Paul LePage, the former governor of Maine, said so directly early this year. "What would happen if they do what they say they're gonna do is white people will not have anything to say," he said during a radio interview. “It’s only going to be the minorities that would elect.”

Popular opinion about the wisdom of popular opinion is also divided along party lines. A poll last year by the Pew Research Center found that a 55 percent majority supported picking presidents by popular vote, compared with 41 percent who preferred keeping the Electoral College. By party affiliation, 75 percent of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents favored a switch to the popular vote, compared with 32 percent of Republicans and GOP-leaning independents. Those majorities held no matter the location of the respondent. Democrats from both blue states and red states preferred the popular vote, while Republicans from red and blue states preferred the Electoral College.

Which explains why the subject continues to come up in the speeches of Democratic contenders for president, even though the office for which they are running has no power to change the future of the Electoral College. It is among Warren’s biggest applause lines, as she tells audiences from one state to another that the current system makes it likely they will be ignored.

“We get to a general election for the highest office in this land, and no presidential candidate comes to Alabama. Or to Mississippi,” she told the crowd at a Birmingham, Ala., rally in March, during a three-day swing through the South. “Your vote just doesn’t count ... and that is wrong.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: