Why the Republican health care bill is doomed to fail — even if it passes

The old Superman comic books used to feature a character named Bizarro, who looked exactly like the Man of Steel, except for his blocky, Frankenstein-like features and the fact that everything about him was reversed. Whereas Superman could burn things with his eyes, the lumbering Bizarro could freeze them; while Superman’s X-ray vision couldn’t handle lead, Bizarro’s could penetrate only lead. You get the idea.

That’s the image that kept popping into my head this week as I watched Republicans hurtle their way toward an ill-conceived overhaul of the health care system. In a sense, what Republican leaders are frantically trying to push through Congress is the Bizarro health care plan — a mirror image of the law it would replace, patched together from spare parts and castoff ideas.

They now seem bent on making exactly the same mistakes Democrats did in 2009, but in exactly the inverse way.

At about this time eight years ago, I was hanging around Capitol Hill and the White House, putting together a preview of the looming health care fight for the New York Times Magazine. (The piece holds up pretty well, I think, but judge for yourself.)

The pivotal Democrat on the Hill then was Max Baucus, the Montana senator — and later President Obama’s ambassador to China — who chaired the Senate Finance Committee. Like Obama, Baucus thought CEOs, health care providers and politicians who had once opposed reform could now be persuaded to support it, as long as the plan promised to get soaring costs and federal spending under control.

And Baucus told me that any new law had to have at least some measure of bipartisan support, even if that required painful compromises. That’s because no piece of massive social legislation had ever been perfect from the start, and in order to preserve and fix it, you needed at least a few members of the minority to be invested in its success.

A transformational law of this size, Baucus said, would be “unsustainable” if one party decided to enact it alone.

The problem for Baucus was that most Democrats, especially in the House, didn’t care at all about corporate competitiveness and public debt. They cared about bringing down the number of poorer Americans who couldn’t afford insurance, and they weren’t open to painful fiscal choices in order to get that done.

So while Obama and his congressional allies sold their plan to industry and the public as an economically necessary reform that would “bend the cost curve,” the law they ultimately passed was really more a wealth transfer program that birthed new regulations and taxes in exchange for expanded coverage for the poor and some middle-class protections — a program very much in the tradition of the Great Society.

The most difficult decisions involving public spending were pushed off years into the future, for some other group of politicians to worry about. And of course, as it turned out, Democrats ended up passing the law along strictly partisan lines, using a budgetary gimmick known as “reconciliation” to help it along.

This wasn’t their call, to be fair; they really weren’t given a whole lot of choice. But what all of this meant, practically speaking, is that Baucus was right — the law was probably politically unsustainable from the start.

What came to be known as “Obamacare” was wildly successful in reducing the number of uninsured Americans by more than 20 million, but the public saw little of the economic benefit it was promised. (Although in truth, health care costs have risen more slowly than they might have otherwise.) Democrats couldn’t make necessary fixes in the sprawling law, because no one on the Republican side had any interest in seeing the law fixed.

Jump ahead now to where congressional Republicans are this week with their American Health Care Act — which is precisely the upside-down version of where Democrats were eight years ago. Whereas Democrats took a bill that was principally about expanding health care and dressed it up as an economic measure, Republicans are taking a plan that’s almost entirely about economics and pretending it has something to do with health care.

They may advertise their bill as a market-based solution to health care inequities, but in fact, what Republicans really care about right now is shedding the new revenue and spending in Obama’s health care law — specifically by repealing taxes and eliminating subsidies for the poor and the Medicaid expansion in the states.

President Trump has promised that “you’ll see rates go down, down, down and you’ll see plans go up, up, up,” and, in distinctly Trumpian terms, that the new system will be “a thing of beauty.”

But the Congressional Budget Office, which is led by a Republican appointee and has a slightly better record than Trump when it comes to veracity, estimates that the plan will cost 24 million Americans their health insurance while saving the government more than $300 billion over the next 10 years.

This time there’s not even a question of bipartisanship. Republicans have been plotting a three-stage legislative process, including a reconciliation measure of their own, to pass their plan without a single Democratic vote — although it’s becoming increasingly unlikely that they will settle anytime soon on a plan that wins over both House conservatives and Senate moderates.

The problem — especially if you’re one of those moderates who actually care about governing and have to get elected statewide — is that the Bizarro health care bill wouldn’t be any more lasting than its predecessor.

Before long, the public would figure out that the law isn’t going to do anything to make coverage more affordable or the choices more vast, as promised, but rather the opposite. Eventually, the popular protections that Republicans say they’ll keep are likely to become unworkable without mandates and subsidies.

Mostly the bill would spare some small businesses and wealthier Americans from paying additional taxes and cut back the Medicaid rolls. The issue of what to do about the uninsured would roar back into the public debate.

And good luck trying to amend the bill in ways that would mitigate its harshest effects, because Democrats may well gain seats in the ensuing elections, and they’re not going to feel the slightest motivation to help clean up the mess.

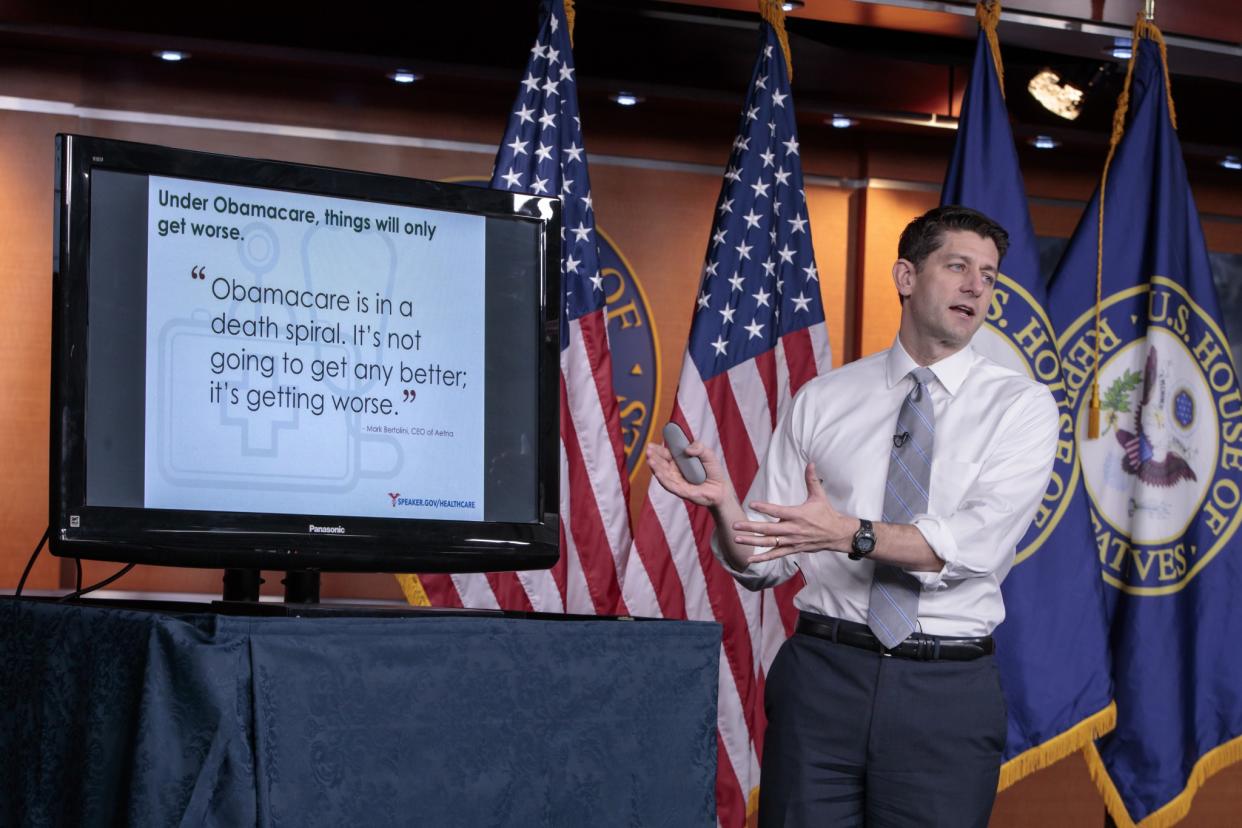

In some ways, Republicans are in a more precarious position with the Bizarro bill than Democrats were in 2009. Obama, at least, managed to cobble together support from insurers and providers, which muted some of the criticism when premiums started to rise. Trump and Paul Ryan, the House speaker, haven’t even tried to assemble a coalition.

You have to remember, too, that Republicans are playing with something here that neither party has ever attempted on such a scale before: a rollback of benefits the public already has. It’s one thing to ram through a program with lots of subsidies and new rights attached. It’s an untested proposition to unilaterally take that stuff away.

Here’s what we do know: With a policy area as complicated as this one, and as reliant on theories about how the markets and consumers will respond to various incentives, you’re never going to pass one law and be done with it. Responsible governing in Washington — if we can still conceive of such a thing — means being able and willing to reassess and adjust to reality as time goes on.

Democrats were never going to be able to do that because of the dubious ways in which they sold and enacted their law. And Republicans won’t have that option, either, even if they manage to come up with something that satisfies their dueling factions.

Superman and Bizarro never actually resolve anything. They just retreat to their parallel universes and live to fight again.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: