Can Lower Manhattan survive climate change? New York's sea level rise plan faces pushback

This is the second article in a Yahoo News series on how U.S. cities are dealing with the threat of sea level rise.

NEW YORK — Jainey Bavishi, the woman tasked with overseeing a new $10 billion plan to save Lower Manhattan from sea level rise, has plenty of reasons to worry. As another hurricane season kicks off, the bulk of the proposed barriers inspired by Superstorm Sandy’s destruction remain in the planning phase, and Bavishi knows that each passing day diminishes the motivating potency of that traumatic event.

“It’s human nature. Memories are short,” Bavishi told Yahoo News, standing in Battery Park with the Statue of Liberty’s fog-shrouded silhouette visible in the harbor behind her. “A lot of this engagement is to try to make sure we never experience another Sandy-like event again.”

While cities like New Orleans and Houston have had to confront the consequences of sea level rise in the wake of historic storms, devising their own tailored solutions to the problem, others remain uncertain how it will creep in and wreak havoc on daily life in the decades to come.

New York’s dystopian preview of a climate change future arrived on Oct. 29, 2012, when Sandy’s 14-foot storm surge swamped much of the five boroughs, killing 44 people, crippling the subway system, inundating 17,000 homes, destroying 250,000 automobiles and knocking out power to nearly 2 million people. All told, Sandy caused $19 billion in damage in the city, a toll that doesn’t include long-delayed subway repairs. Although only a Category 1 storm after laying waste to the Jersey shore, Sandy erased neighborhoods from Staten Island, redrew others in outer Brooklyn and Queens, and, like the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks before it, brought Lower Manhattan and Wall Street to a halt.

As with the steady spread of wildfire damage across the American West, or the recurrence of what used to be considered “100-year” storms, Sandy’s devastation too had been predicted. Scientists on the New York City Panel on Climate Change, or NPCC, had warned elected officials since 2008 that global warming and its accompanying sea level rise presented heightened risks to a city with 251 miles of densely populated shoreline. But until such dire predictions actually come true — and sometimes even after they do — they’re simply too easy to discount.

For the neighborhood the nation’s financial industry calls home, however, ignoring the threat is not an option. The ground elevation in Lower Manhattan ranges from 7 feet above sea level between the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges to a high of 13 feet at the base of the Freedom Tower, the building on the site of the old twin towers. While the waters lapping at its shores have risen by roughly 11 inches since mankind began spewing carbon into the atmosphere at the start of the industrial revolution, over the next 80 years, they are predicted to jump precipitously — by just over 6 feet, according to the NPCC.

Klaus Jacob, a research scientist at Columbia University who also serves on the NPCC, helped compile the startling 6-foot estimate, which, he notes, is much more likely than not to come to pass.

“What we’ve chosen to do is to make a probabilistic forecast. You can choose the level of certainty, or safety, if you like,” Jacob told Yahoo News. “We have different percentiles and the one that’s most commonly recommended to be used is the so-called 90 percentile. That is to say that if you had 100 different forecasts [based on different assumptions,] 90 would be at or below that level and 10 percent would be still above.”

In its most recent assessment to the city, however, the NPCC also noted the possibility that, depending on how quickly the ice in Greenland and Antarctica continues to melt, New York could see as much as 9 feet of sea level rise by the end of the century.

“We felt obligated to point out that there is actually a scenario out there that is less likely than the 90 percentile but we ought to mention it,” Jacob said.

The year after Sandy hit, then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg pledged $20 billion to make the city more resilient to the consequences of climate change. “We can do nothing and expose ourselves to an increasing frequency of Sandy-like storms that do more and more damage, or we can abandon the waterfront,” Bloomberg said.

The Danish architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group won a design competition with a proposal called “The Big U” that was to encircle Lower Manhattan with a combination of seawalls, sloping barriers and green spaces meant to offer protection from future storm surges. But in September, following years of planning and community meetings, the plan to begin the 10-mile barrier ring with an 8-foot berm bordering East River Park was abruptly halted so as to avert a lengthy shutdown of traffic lanes on the FDR Drive. In its place, Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration announced the city would dump more landfill over the existing park, creating a narrower 10-foot high obstruction to keep seawater from again reaching the streets of the Lower East Side.

But that wasn’t the only change. In March, citing the threat from future Sandys, de Blasio unveiled another modified plan to protect Lower Manhattan and spare it from traffic Armageddon. Although de Blasio borrowed many of the suggestions from his predecessor’s plan, the centerpiece of his proposal involved a $10 billion extension of Lower Manhattan up to 500 feet into the East River — which is approximately 6,000 feet wide beneath the Brooklyn Bridge — so as not to disrupt the highway or underground subway and power lines that crowd the neighborhood’s eastern edge.

“We’re going to build it, because we have no choice,” the mayor wrote in a foreboding article in New York magazine that previewed his proposal.

‘A logical calculus’

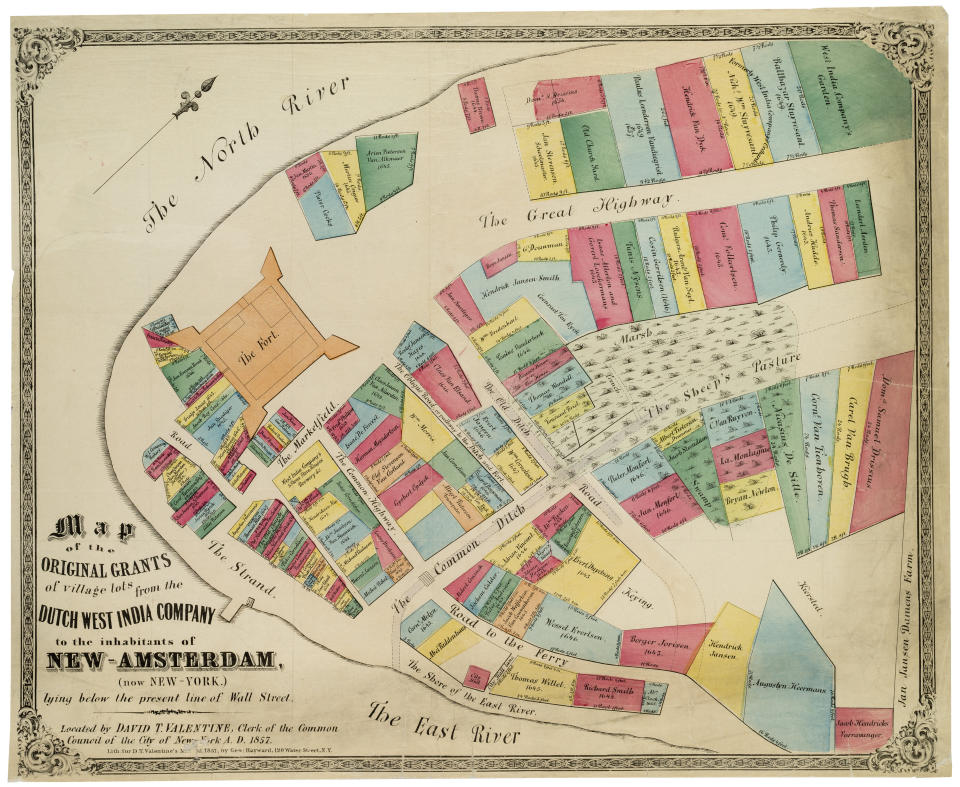

Settled by the Dutch West India Company in 1624 and originally called New Amsterdam, Lower Manhattan was, for centuries, an ideally situated port. Bordered by water but sheltered from the open ocean by New York Harbor, as the city exploded northward, its shoreline was also extended via landfill, eventually nearly doubling the area on the island’s southern tip.

By the time Bavishi was appointed the director of the Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency in 2017, Sandy had laid bare the precariousness of the low-lying landfill extensions in a neighborhood that accounts for 1 in 10 jobs in the city.

“Lower Manhattan is a financial engine for the city,” Bavishi told Yahoo News as she walked through Battery Park on a foggy Wednesday morning last week. “New Yorkers depend on it for their livelihoods.”

The former associate director for climate preparedness during final years of the Obama administration, Bavishi is experienced at using hurricane damage to formulate a blueprint to avoid future catastrophe. Before a stint as a senior policy adviser at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, she moved to New Orleans in 2005 in the wake of Hurricane Katrina to lead a nonprofit that worked on equitable recovery efforts along the Gulf Coast.

Jacob, however, believes that city officials need to come to terms with Lower Manhattan’s long-term outlook — which might mean giving up on parts of it.

“Why would we put more assets close to sea level when we have other options available that are not being considered?” Jacob said. “I feel that we’re in a long-term denial and we are talking about resilience but it’s unsustainable. Sustainability is defined as doing something good for current generations without producing liabilities for future generations and that’s exactly what this is not. This provides more liabilities for future generations.”

Rather than enter an expensive and unwinnable race against the ocean, Jacob wants the government to consider relocating the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the New York Stock Exchange to higher ground. While he applauds the actions taken by the Metropolitan Transit Authority to seal 3,700 openings into the subway system and Con Edison’s $1 billion upgrades since Sandy, he’s also pessimistic about the neighborhood’s future.

“It’s just not sustainable, period,” Jacob said.

Bavishi, whose office relies on the NPCC’s scientific consensus and who has often sparred with Jacob over his personal assessment, is equally emphatic about her conviction that Lower Manhattan has to be protected.

“Relocating the economic hub of the entire nation is impossible,” Bavishi says. “You can’t relocate Lower Manhattan. The only option is to protect it.”

Nine feet of sea level rise, compounded by storm surge, would pose an enormous challenge to the seawalls and berms the city intends to build. But Bavishi said the design envisions raising them even higher in the future if necessary.

“We’re doing what we can to make sure that the investments we’re making are adaptable. We know what the trend is: The sea level is going to continue to rise,” Bavishi said. “While we’re using the projections that we have the most confidence with now, we don’t want to have to rip up these projects and rebuild them in order to protect these communities from future sea level rise. Resilience is a process, not an outcome.”

Robert Kopp is a climate scientist and professor at Rutgers University who also serves as one of the directors of the Climate Impact Lab, which assesses the economic risks of climate change. Like Bavishi, he doesn’t believe moving the financial sector to higher ground makes a lot of sense, given current projections.

“I think Manhattan is defensible across a range of sea level rise predictions,” Kopp said. “But there is a breaking point, and that’s why you need the contingency plans. There surely is a point where you either need to relocate people or you have to redesign the area to accommodate flooding.”

Either because human beings lack the imagination to fully grasp the enormity of the challenges posed by climate change, or due to the variability in modeling for just how fast the polar ice caps will continue melting, urban planners seem fixated on how high waters will rise by the end of the century. But Kopp points out that the buildup of carbon in the atmosphere means that sea level rise will likely continue past then, unabated.

“The implications of zoning decisions do not end in 2100, so we really do need to be thinking about these high-end numbers which may be unlikely in 2100 but will happen sometime in the lifetime of Manhattan,” Kopp said. “We hope it’s very far into the future, but it might not be.”

Manhattan native Peter Gleick, one of the world’s leading experts on water and climate change, says that if he were buying property in New York City today, he wouldn’t buy at an elevation lower than 20 feet.

“It’s not the incremental rise in sea level that kills you. It’s the storms. It’s the extreme events on top of sea level rise,” said Gleick, who co-founded the Pacific Institute, in Oakland, Calif. “So look at Sandy. We’ve had 4, then 8, then 11 inches of sea level rise over the course of 100 years, but it’s not until you get the storms on top of sea level rise that you realize the systems you’ve built are vulnerable.”

Like Jacob, Gleick believes that it may take insurance companies hiking rates, or banks refusing 30-year mortgages, or, worse, one or two more hurricanes the size of Sandy, before many people will take sea level rise seriously.

“Donald Trump can call climate change a hoax, but the financial institutions can’t afford to do that. They deal with reality,” Gleick said.

A 2014 study the city commissioned from the Zurich-based reinsurance company Swiss Re that found that, thanks to sea level rise, if no defensive actions were undertaken and a storm of Sandy’s size and strength were to hit New York in 2050, it would cause $90 billion in damage, a figure that makes the price tag of extending Lower Manhattan into the East River feel like a bargain.

“It’s a logical calculus, but one of the challenges is that humans have never dealt with sea level rise on the time scale that we now expect it to happen,” Gleick said. “It’s one thing to say Lower Manhattan’s economic value is so high that we have to build physical protection and it’s another completely different thing to actually do that quickly and effectively enough to protect that value.”

‘An extremely motivating factor’

At the East River’s ever-evolving shoreline, Bavishi stands on an observation deck on Pier 15 and gestures at the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges. Urban design from decades past that crammed skyscrapers and the FDR Drive just feet from the water’s edge have left the city little choice but to manufacture new ground in order to keep Lower Manhattan above water.

“The shoreline has to be extended 50 to 500 ft. That’s a big range, so we need to figure out exactly how far we need to go out into the water,” Bavishi said. “We need to figure out how that will be financed and how we will use that land.”

Securing federal funding to help New York pay the estimated $10 billion bill to wage war against the water won’t be easy. President Trump, after all, has labeled de Blasio — who announced his own White House bid last month — a “joke” and called global warming “a hoax.”

“I watched as the Trump administration unraveled all of the climate advancements that we had made during the Obama administration,” Bavishi said. “But I feel fortunate that I landed in a place where I could continue our work full steam ahead. We’re not waiting for Washington to act. We’re taking matters into our own hands.”

Because so many details have yet to be worked out — let alone building anything — temporary barriers will have to suffice to keep Lower Manhattan’s eastern shores safe until at least 2025. This summer, Bavishi’s office will begin accepting requests for proposals from companies bidding on the project. With de Blasio’s term ending in 2021, however, it’s unclear how long the new plan will endure in its current form. But Bavishi’s impetus to see the projects through to completion extends beyond her position in the mayor’s office. This year, she gave birth to a daughter.

“She’ll be 80 in 2100. I’m a fairly new parent, so that’s an extremely motivating factor,” she said. “I’d been doing this work for a long time before I became a parent and it gives me new urgency to get this stuff done.”

Clear-eyed about what still remains be done before Lower Manhattan can, at least for a little while, consider itself out of harm’s way, Bavishi points up at what feels like an impossibly narrow skyscraper under construction just across the FDR Drive. Approximately half of the building is still without outer walls, the cinder-block and orange construction plastic visible on the upper floors. “They found out that building is tilting 3 inches,” she said of the project titled “One Seaport,” a 21st century cautionary tale on the fallibility of engineering.

Asked how they were going to fix the problem unrelated to the rising seas, she shrugs. “No idea.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

‘It’s over’: Miami Beach tries to outrace climate change’s rising seas

In quest for Gen Z votes, 2020 could be the year of the influencer

How Trump's embrace of a rogue Libyan warlord sparked a humanitarian catastrophe